Bombs Falling on My Hometown

Self Portrait in Soviet School Uniform, oil on canvas, 2003

Self Portrait in Soviet School Uniform, oil on canvas, 2003

Kiev is a beautiful city. That is what my grandmother tells me with tears in her eyes, every time it comes up. It is hilly and green, she says, and full of magnificent, historical architecture. In the fall the leaves dress up in orange and red, and in the spring magnolias bloom. But I don’t remember the architecture, the hilly streets, or the magnolias. My memories of Kiev are more sensory. The smell of leaves crunching beneath my booties, the hard crust and warm insides of Ukrainian rye bread, how our tiny local vegetable store smelled of cabbage, the rhythmic thump of the Trolleybus.

Though I was born and lived for the first seven years of my life in Kiev, I never lived in the country of Ukraine. I did not live in a Democratic country, certainly not in one where a Jew could be elected president. The country we left was an oppressive, totalitarian regime, in which my parents were actively persecuted for the crime of dissent and of being Jews. My parents and I left the Soviet Union as refugees in 1989.

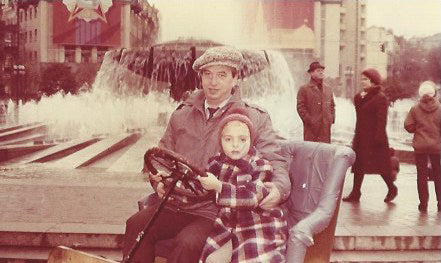

My parents and I in the Soviet Union, 1987

Now I sit in my Los Angeles living room watching bombs rain on my hometown and I can’t believe my eyes. Distant though I may be and feel from Ukraine, the footage of crowds of terrified refugees sheltering in train stations is eerily familiar. Cell phone footage of the apartments rattled by nearby explosions look just like the one I grew up in, down to the Persian rug and crystal ashtray on the coffee table.

My Babushka feeding me in our Kiev kitchen

My 91 year old grandmother has been crying since the bombs began to fall. She and my grandfather spent 61 years of their lives in the Soviet Union, where they suffered through World War II, hunger and cold, living conditions and levels of oppression, discrimination, and persecution that are unfathomable to those of us fortunate enough to live in the United States in this day and age. Twenty-six of our relatives were buried alive in Babi Yar. “How many children will die?” My grandmother keeps asking. “This is just like when the Nazis came. We were saved because we were evacuated. But who will save them? There is nowhere to go. ”

My grandfather and I in the Soviet Union, August 1987

Millions of lives are on the line because an authoritarian maniac wants to rebuild the horrible country we escaped. But in America, our memories and attention spans are short. College kids wear kitsch Soviet Union t-shirts or CCCP pins like it’s cool. And this isn’t new. Back when I was in art school, I balked at a fellow student who walked into class in a KGB t-shirt. KGB!! Perhaps her Gestapo t-shirt was in the laundry. But can you blame her? Stalin and Communism was barely mentioned in my grade school curriculum in suburban Chicago.

I can’t shake the feeling that this week the world has changed. It is the same way I felt walking downtown Chicago the morning of September 11, 2001 looking up at the sky and wondering if any airplanes were coming. We live in the most powerful country on earth, and yet here we are looking on impotently, not knowing how to help those in harm’s way.

I implore you, don’t look away. Don’t put a Ukrainian flag on social media and forget all about it. When someone somewhere uses the wrong language or posts the next wrong tweet, don’t be distracted by the outrage bandwagon. This is reality now. When you take your kids to soccer practice this weekend, remember that Ukrainian kids were playing soccer last weekend too. When you kiss your kids good night, think of the fathers in Kiev kissing their kids before leaving to fight for their freedom. And when the news cycle moves on, remember that the world has changed. What we pay attention to matters. A dictator has just changed the rules of the game, and he wants us to be distracted and look away. We mustn’t let him win.

Leave a comment